A park as racial redress, the white spatial imaginary, and diversity ideology

Unity Park in Greenville, SC *or* Debriefing my PhD coursework this semester

This semester I took three classes: Race & Place (a Sociology course that considered, you guessed it, the role(s) of race and racism on place (material, immaterial, corporeal, etc) and the role(s) of place on race and racism), Public Space & City Life (an Urban Design/Architecture class that had a surprising amount of Sociology literature on the syllabus), and Research Design (a required Sociology class that helps second year PhD students prep for collecting data and writing their MA project/paper.

Because I somehow believe in working harder, not smarter, and maybe because I— like anyone else who willingly signs up to be in advanced school for the entirety of their twenties— am a bit of a masochist, decided to do all of my assignments for this semester on the topic I want to focus on for my MA paper: Unity Park.

Friends from Greenville will know exactly what I’m talking about and can probably guess at why I’m so interested in it. But for those of y’all who don’t know, I’ll give you a quick run down:

Unity Park is a recently developed park just outside of downtown Greenville, South Carolina. The park sits right on the edge of multiple historically Black neighborhoods which have seen significant demographic and landscape changes over the past decade, most notably severe loss of its Black residents. You can guess why, and you probably already know, but I’ll tell you: gentrification.

Where the park sits used to be land shared by two segregated parks. In the 1930s, Black residents petitioned the City Council to invest in the public park infrastructure and the city said: big fat no. Of course, over the years, the park, just like neighboring Black communities, would be intentionally disinvested from by the city, deemed “blighted”, etc. So, 80some years later, knee deep into our first Trump term, when the city is working on “revitalization” plans which have already drastically changed the downtown into a bustling commercial district, and renamed another historically Black neighborhood as “The Village” and “the Arts District”, catchy city-and-white-business-curated identities that long-time residents have called out, the idea of a park for redress— for reconciliation and racial inclusivity sounds great!

And in 2022 when the park is unveiled, longtime Black community leaders are loving it! Talking about how this park is an answered prayer, a true representation of the city’s growth and change in values, a “wrong made right.”

But is it?

I got super interested in George Lipsitz’ conceptualization of the white spatial imaginary while taking my Race & Place class and I learned about diversity ideology (as conceptualized by Sarah Mayorga-Gallo) which seems to describe my critique of Unity Park and why it rubs me the wrong way.

The white spatial imaginary referring to the ways white Americans consciously and unconsciously structure their physical and social environments to maintain and reproduce racial privilege, and diversity ideology as a racial ideology that even affects the built environment and symbolic landscape (as I’ll explain through my example of Unity Park) by promoting the idea of multiculturalism and inclusivity but often in ways that are superficial or performative, and that center whiteness and white comfortability.

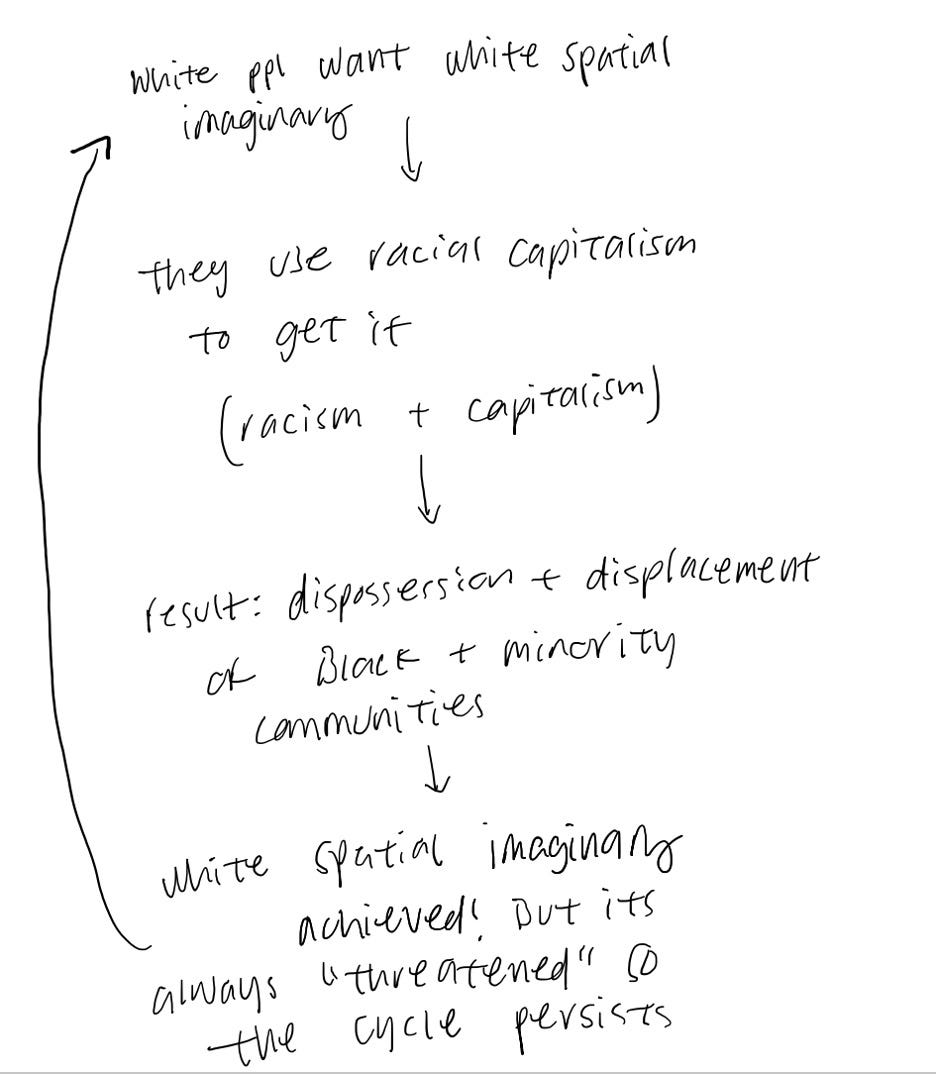

In my final paper for Race & Place, I used Unity Park as an example to show the relationship between diversity ideology and the white spatial imaginary. In a nutshell I add to Lipsitz’ argument that the production and preservation of the white spatial imaginary leads to and is predicated on the displacement and dispossession of marginalized people and communities. I add, through the context of Unity Park from 2020-2024, that diversity ideology, even through symbolic acts of redress which are meant to repair harm and promote equity, reinforces the white spatial imaginary.

A handful of folks asked for my paper out of curiosity— this park is still a controversial subject in my hometown. I’m still thinking through Unity Park as a case study and somewhere I’d like to do more research on the intersections of diversity ideology, conflicting symbolic landscapes (see: larger confederate landscape within less than 6 miles of the park itself), and third/community spaces. This is where my still-hypothetical-at-this-point MA paper is headed. But for now, I’ll leave you with this early brain child— which I must say is largely supported by data from Ken Kolb and the Shi Institute. (Ken, if you’re reading this, I’m still salty you gave me a B on my paper in Soc 101, but I’m very grateful for your research and all you do for our community! My public Sociologist aspiration fr!)

I’ve had a very tender and itchy feeling all semester realizing that so much of my intellectual curiosity keeps looping back to Greenville, early inklings I had as a teenager, and the same kind of work that mentors from my undergrad have been doing and are doing that I didn’t realize!! Why are there so many scholars across disciplines interested in symbolic landscapes and place making in Greenville, SC?! I don’t know, but it all feels meant to be.

Unity Park: How Diversity Ideology Reinforces the White Spatial Imaginary

Introduction

In the summer of 2020 when a new park just outside the heart of downtown in the historically Black neighborhood of Southernside was announced, the response was something between excitement for a new public resource and long-instilled skepticism after all previous city efforts to “revitalize” downtown in the last decade meant a complete overhaul of the neighborhood landscape that long-time residents were familiar with: new streets, new businesses, new expensive housing, an influx of white folks from God knows where, multiple zip code changes. The three downtown historically Black neighborhoods: Southernside, Sterling, and West Greenville were created how most historically Black neighborhoods are made: segregation, discriminatory housing policies, and white flight (Kolb, Winiski, Hayes, Lippert. 2023). Intentional disinvestment and neglect from the city left these neighborhoods with declining infrastructure and lacking the resources that the white communities, just streets away, had. Revitalization sounds like exactly what residents had been advocating for years. But these developments too frequently left out the voices of residents, demolished homes and businesses, and ultimately led to many longtime residents being priced out of their homes and community. The most recent example had been West Greenville, once a working-class Black neighborhood, now a designated “arts district” complete with, yes, artist studios, an artisan butcher, a handcrafted pasta maker, and other small and very niche boutique shops, eateries, and yoga studios—and, noticeably, less and less Black residents. Skeptical residents wanted to know, what was stopping this same thing from happening to Southernside?

The White Spatial Imaginary refers to the ways white Americans, consciously and unconsciously, structure their physical and social environments to maintain and reproduce racial privilege (Lipsitz 2011). A spatial imaginary refers to the “socially shared moral geographies [that] have long infused places with implicit ethical assumptions about the proper forms of social connection and separation.” (Lipsitz 29) Rooted in colonialism and exemplified in the development and trajectory of suburbanization, the white spatial imaginary persists into the contemporary context as exclusionary laws and discriminatory practices, as well as particular development/design choices that promote segregation and structure inequality in the built environment and the lived experiences of residents. In this way, the white spatial imaginary is intentionally man-made with tangible consequences and outcomes, but it is also an aspiration that fatally connects race, place, and power to prevent people of color from equal opportunities (Lipsitz 2011, 61) Diversity ideology, as a widespread national racial ideology, affects the built environment and symbolic landscape by promoting the idea of multiculturalism and inclusivity but often in ways that are superficial or performative, centering whiteness and white comfortability (Mayorga-Gallo 2019). When diversity ideology is paired with a commemorative (symbolic) landscape that communicates social narratives and values, The result is communities that appear progressive in the ways their built environment is structured, and in the images presented through the symbolic landscape, but that uphold or exacerbate systemic inequities.

Unity Park would be different, answered City Council, because it was a park designed for everyone— “The people’s park”, they called it. It would honor Black residents who advocated for the development of a park at the same site close to a century ago. It would serve a diverse constituency and be a welcoming public space for all residents. And it would be a reminder of the city’s values of diversity and inclusion. But according to a report published in 2023, over the past 30 years, Greenville’s historic Black neighborhoods have seen a 53% decline in the number of Black residents while the white population in those same neighborhoods has nearly doubled, and the 1-mile radius surrounding Unity Park has lost 47% of its Black Residents (Shi Institute 2023). Displacement and dispossession are key consequences of a functioning white spatial imaginary, and diversity ideology only visually obscures these consequences. Using the case study of Unity Park, I’ll explore the relationship between diversity ideology and the white spatial imaginary and how this racial ideology complicates Lipsitz’ ideas on how to address it.

The Case

Greenville, SC

In a valley at the bottom of the Blue Ridge Mountains, on Cherokee land, sandwiched between Charlotte, North Carolina and Atlanta, Georgia, Greenville, South Carolina is a mid-sized and rapidly growing and changing Southeastern city. The Reedy River, which runs through the heart of the city, made the city a textile industry hub in the 19th century. With the decline of textiles in the mid 20th century, the city transitioned to manufacturing. In the 1990s, BMW established a manufacturing plant just outside of the city which supported a massive revitalization effort to develop the city into what it is today. The development of a lively and commercial downtown with a tourist-attracting suspension bridge over the Reedy River’s main waterfall and surrounding park was the first major overhaul in the city’s reimaging.

The city is in the deep South, though, and has a difficult social and cultural history still tied up in the consequences of segregation and systemic discrimination. Schools in Greenville would not be desegregated until the early 1970s and the most prominent Black high school in the wealthier Black neighborhood of Sterling would be “mysteriously” burnt down in the 70s. This is the high school and neighborhood where Jesse Jackson grew up and where he was among Black students who staged a sit in at the downtown public library, challenging segregation.1 Activism has a life in the city, and Greenville narrativizes itself as a progressive and diversifying city as it experiences significant growth and development, but outcomes of activism can be slow-moving and disconnected from the moment of the action. Though, as Greenville models its development on nearby major cities, new additions to the commemorative landscape honoring Black residents support the presentation of the progressive and diverse city, but also create a contradictory symbolic landscape. Like many other southern cities, Greenville has at least one confederate statue, roads named after white supremacists, and high school’s whose names and identities are centered around local confederate and segregationist history. Even with public contestation, including 10,000 signatures to rename the confederate namesake of a local high school, it seems many residents are either unaware of the history behind the namesakes of the roads they drive on every day, the neighborhoods they live in, and the schools their children attend, or they do not care and/or prefer to simply not address them. The South Carolina Heritage Act, a law passed in 2000, makes it so changes to the commemorative landscape concerning confederate and civil rights monuments, statues, and namesakes require a 2/3rds majority vote in the South Carolina statehouse over 100 miles away in the state’s capitol.

The development of Unity Park coincides with pressure from local and national calls for racial reckoning and justice. Furman University, the nearby private college, responded to a Slavery and Justice Taskforce that highlighted the university’s direct involvement in slavery, segregation, and continued disproportionate campus experiences and outcomes for Black students with renaming academic and residential halls to distance from the glorification of the university’s white supremacist namesake, landscape shaping, statue erecting, and commemorative institutionalization to honor Black community members. Data collected and shared on the city’s relationship with gentrification and outcomes related to the displacement of Black residents has been led by scholars at the university and advocacy efforts have been supported in partnership with the university. This relationship is important to note because it is one of the few reasons why there is data on the changes in the city and acts as a safeguard against the gaslighting that happens when diversity ideology is the primary driver in enforcing the white spatial imaginary. This will be further discussed in the White Spatial Imaginary section.

Unity Park

Featured in the National Recreation and Park Association magazine, an article introduces the park as “the latest jewel on an emerald necklace.” It continues, “A century in the making, the 60-acre park pays homage to the legacies of the two historic neighborhoods surrounding it — Southernside and West Greenville — where residents describe a painful history of segregation, as the land once served as a buffer between the predominantly white downtown and the Black communities” (Eaker and Fletcher 2022).

The neighborhood where the proposed park would sit already held a park once. The overgrown patch of blanching grass and always-flooded concrete lot-- sitting beside what probably was an old warehouse but is now a yoga studio and a craft beer and burger joint—was once Mayberry Park, a segregated park for Black children on the edge of Southernside built in 1925. In the mid-1930s, a Black community leader wrote an op ed to the Greenville newspaper and gathered signatures from the neighboring Black communities that the park jointly-served to petition the city council to invest in developing the park to create a safer playfield for children. The council denied the request and eventually the disinvestment from the city led to the park becoming virtually unusable— with a general lack of infrastructure, constantly flooded and muddy.

In 2016, as other neighborhoods were being to gentrify under revitalization efforts, the development for the park began with joint-interest in restoring the neglected river along the 22-mile Swamp Rabbit Trail greenway which connects Greenville to the neighboring town of Traveler’s Rest and answering calls to develop affordable housing. In between the early development and the grand opening of the park in 2020, community workshops were held with residents in the nearby neighborhoods. Councilwoman Lillian Brock-Flemming whose mother was a prominent community leader from Southernside and Mary Duckett, long-time resident and president of the Southernside neighborhood association, would become two of the parks most visible Black supporters. In a May 2022 interview at the park right around the first weeks of opening, a white news reporter says in introducing Duckett, “It’s hard for me not to cry because I know how much this park means to you.” When asked what the park means to her, Duckett responds, “This is what heaven is going to look like. It’s going to be peaceful. People are going to get along together. It’s a healthy environment. When I came up in this neighborhood this was really an atrocity. No one living this close to downtown… should have had to live in an area with junk yards and a fire range and a polluted river…” Duckett goes on to say after being prompted to talk about getting donors on board with the park’s development, “It was important to [tell private park donors] the good, the bad, and the ugly. And the ugly parts I told them first so I could play on their hearts and let them know what conditions we lived in.” As Duckett says she does not want to cry, the news reporter encourages her to cry, “I mean, we’re all really about to [cry]. This is a wrong made right!” Duckett continues, “This is never going to be a Black and White America ever again. This is a place of inclusion. No segregation. Inclusion.” (WYFF News 4 2022)

This interview sums up the narrativization of the park: a symbolic act of redress, visualized with commemorative naming-efforts to honor Black community members such as Brock-Flemming’s mother and Duckett herself, a mural of E.B. Holloway, the initial park petitioner, on the park-facing wall of the welcome center, and 10-foot-tall sign that says “UNITY” at the front edge of the park. Much of the news reporting on the development of the park centers around “a wrong made right” including the city’s reported investment into the development of affordable workforce housing and senior living nearby the park. This is the city’s answer to fear and critique of gentrification, but residents question the success of this intervention as the units and the terms of eligibility are too limited to address the current rates of Black and low-income displacement. [new citation] Specifically in the area directly around Unity Park, data shows that the total black population dropped from 8,878 in 1990 to 4,666 in 2020 (Shi Institute 2023) and while the median white household in Greenville makes 2.8 times more income than the median Black household, the Black poverty rate is 34.4%-- almost five times that of the white poverty rate (Kolb 2023). In a Special organized with the Greenville News, Sociologist Ken Kolb writes of the conflicting findings of the outcomes of Greenville’s revitalization:

Today, the city is finally investing in communities it once abandoned. It is following the same template of 40 years ago: calming traffic, widening sidewalks, and unveiling greenspaces. Unfortunately, the consequence of this new investment — this promise redeemed — will be a further increase in rents, meaning more homes will be out of reach for the majority of Greenville’s Black population.

Efforts are being made to offer more housing at reduced rates, yet they are not enough to change our current demographic trajectory. Even subsidizing new units aimed at people earning 80% — or even 60% — of the overall area median income will fall short. Those rents will still be well above what the median Black family can afford.

Our current strategy to increase “affordable housing” will not slow racial displacement in the city.

This may not be the story of Greenville’s “revitalization” that we read in promotional materials, but it is one that is backed up by facts and data. And the one we need to talk about.

In this way, the park has an inherently contradictory nature as a symbolic act of redress while contributing to severe rates of dispossession and displacement in the same community and of the same people the park intends to redress.

The White Spatial Imaginary

“The lived experience of race has a spatial dimension, and the lived experience of space has a racial dimension” (Lipsitz 2007, 12). The white spatial imaginary, as conceptualized by Lipsitz, encompasses the built environment— how space is designed and structured to support or squash interaction—and the intertwined systems of law, politics, and culture that inform and enforce systemic differences in the lived experiences of people based on race. “A white spatial imaginary, based on exclusivity and augmented exchange value, functions as a central mechanism for skewing opportunities and life chances in the United States among racial lines” (Lipsitz 2007, 13).

To the extent that the white spatial imaginary is aesthetic and catered to the desires of white interests, examples of the white spatial imaginary include the classic white suburb, the country club, the debutant ball—these are all microcosms of the larger white spatial imaginary at work. To the extent that the white spatial imaginary structures inequality in the lived experiences of people based on race, the most obvious examples of the white spatial imaginary are seen through the examples of segregation, the formation of racially restrictive covenants, the history and legacies of suburbanization, and the effects of cities’ intentional disinvestment from Black communities.

“The white spatial imaginary idealizes “pure” and homogeneous spaces, controlled environments, and predictable patterns of design and behavior. It seeks to hide social problems rather than solve them. The white spatial imaginary promotes the quest for individual escape rather than encouraging democratic deliberations about the social problems and contradictory social relations that affect us all.” (Lipsitz 2011, 29) But the white spatial imaginary has “created the conditions it condemns” (Lipsitz 2007, 40): “Spatial displacement, dispossession, exclusion, and control shape the contours of racial subordination and exploitation in decisive ways.” (Lipsitz 2007, 16) The calls for addressing “blight” and long-winded plans for “revitalization” are a product of the city’s intentional disinvestment from Black neighborhoods and communities. Through displacement, dispossession, exclusion and systemic control, the white spatial imaginary ensures that racial subordination is both material and spatial. In this way, the white spatial imaginary is also self-reinforcing as it creates a cycle where spatial inequality is manufactured and perpetuated while the resulting inequalities are used to justify further marginalization.

Diversity Ideology

In our post-2020 moment, calls for “diversity and inclusion” have overtaken colorblind racism as the prevailing racial ideology of the United States. Where colorblind racism is predicated on the idea that race is either unimportant and/or structural racism does not exist, diversity ideology acknowledges structural inequality in the abstract, framing exclusion as the cause of racial inequity and fair representation as the solution (Mayorga-Gallo 2019). Diversity ideology creates the opportunity for individuals and institutions to appear like they are following procedures of diversity and inclusion without truly repairing harm and still maintaining the benefits of systemic whiteness (Mayorga-Gallo 2019). In this way, “Diversity ideology creates a logic by which whites can discuss racial inequality or the importance of diversity, while centering their desires, intentions, and comfort” (Mayorga-Gallo 2019, 1794).

How do we Address the White Spatial Imaginary According to Lipsitz?

“…Disavowing whiteness will not be enough. merely removing negative obstacles in the way of democracy will not produce a democratic society. We need to envision and enact new democratic practices and new democratic institutions. To do so, we need to understand the Black spatial imaginary.” (Lipsitz 2011, 50)

The Black spatial imaginary, as a counter-spatial imaginary is based on sociability and augmented use value (Lipsitz 2007). As the white spatial imaginary focuses on exchange value (the monetary worth of space), augmented use value in the Black spatial imaginary seems to refer to the ways in which space develops deeper meaning through collectivism.

Because the Black spatial imaginary is enforced by the white spatial imaginary, its main features— which Lipsitz argue are what can address the ills of the white spatial imaginary— are forged from the constriction imposed by the white spatial imaginary: a reliance on communal social and care networks and strong investment in advocacy/activism to organize politically. Lipsitz idealizes these aspects of the Black spatial imaginary and argues that divestment from the white spatial imaginary will happen with investment in systemic equity and adoption of Black community social norms:

Our primary goal should be to disassemble the fatal links that connect race, place, and power. This requires a two-part strategy that entails a frontal attack on all the mechanisms that prevent people of color from equal opportunities to accumulate assets that appreciate in value and can be passed down across generations, as well as a concomitant embrace of the Black spatial imaginary based on privileging use value over exchange value, sociality over selfishness, and inclusion over exclusion (Lipsitz 2007, 14).

Lipsitz seems to argue for more genuine communal practices, equity and justice for marginalized communities, and more democratic community spaces and civic engagement from community members. “Blackness in U.S national culture has become the master sign of fear of the social aggregate, of the phobia of being engulfed and overrun by some monstrous collectivity. In fearing a linked fate with other people, the white spatial imaginary is innately antidemocratic. The lack of democracy in our society is both cause and consequence of the possessive investment in whiteness” (Lipsitz 2007, 37).

My Contribution

Unity Park makes for a unique case to consider through the lens of the white spatial imaginary because of its curation as a symbolic act of redress for the local Black community. It does not fit Lipsitz’ characterization of spaces within the white spatial imaginary as a homogenous space seeking to hide social problems or discouraging democratic deliberations about such social problems. The park narrativizes itself as a community space with diversity and inclusion as a clear central value as communicated in the design through the symbolic landscape and in its official merchandizing. Homage to the past (also as communicated through the symbolic/commemorative landscape of the park) and open acknowledgment of the city’s denial of basic equal resources to the Black community as the genesis for the park’s development 80+ years later means that the space is showcasing a social problem. And the park’s institutionalization of commemorative events dedicated to remembering that past and its availability to community groups who would like to host cultural events such as Juneteenth celebrations means that it is somewhat open to democratic deliberations about social problems. What explains this is the role of diversity ideology.

On Memory

Diversity ideology, as present in the rhetoric used to narrative the public identity of the park and story of its symbolic landscape, obscures the intentions and outcomes of the white spatial imaginary upon first glance. It is interesting to consider this alongside the intended outcome of symbolic acts of redress. Reparations have become frequent demands of activists. Reparations are concrete and material where apology is symbolic and can be viewed as superficial. Apology, though, is practical, promotes better intercommunal relations, and can allow a sense of “moving on” (Walters 2017). Symbolic acts of redress seem to be a middle ground between reparations and apology, and removals of monuments, name changing, and public acknowledgement and/or apology of past harm, have become the begrudging resolution(s) of city powerholders. These actions can be seen as superficial acts of reputation management (Fine 2013) in response to or brought on by outcry from the public (Turick, Weems, Swim, Bopp, and Singer 2021), and they may be. But these symbolic acts of redress are given meaning through the community’s collective memory, and physical/tangible changes to the built environment directly structure the physical and social environments of residents. Memory is collective, contextualized by our social environments (Clarke and Fine 2010) and our social environments affect the ways in which we remember the past, also distorting what we remember (Zerubavel 1996). Socio-biographical memory allows us to feel connected to events, groups, and communities that may have happened long ago and that we may not have been present for (Zerubavel 1996), which means symbolic acts of redress can have a particularly powerful social utility. Commemorative symbols are stored in institutions and transmitted across generations and stored outside the minds of the individual (Schwartz and Schuman 2000), making understanding symbolism a collective act. “Physical symbols are an expression of who we are and what we value as a community” (Walters 2017). Because diversity ideology is intentionally superficial and rooted in the comfort of whiteness, diversity ideology in conjunction with the symbolic act of redress would seem to nullify any real justice that could have been given through an act of redress. But the tangibility of the choice to alter the physical commemorative/symbolic landscape affects the collective memory and social identity of community members, which complicates how we can measure success of the symbolic act of redress.

This intention of how collective memory is an operating force at the park through the symbolic landscape is also present in the rhetoric used by park supporters like Councilwoman Lillian Brock-Flemming: “We felt that it was important to help tell the story of Unity Park… That means our history will not die,” (Fitzgerald 2024)

On Addressing the White Spatial Imaginary

In his 2007 article on the white spatial imaginary, which is primarily written to and published for and audience of landscape architects, planners, and other land-use professionals, Lipsitz offers a few interventions:

“Serious commitment to implement and strengthen fair housing laws would encourage the development of new kinds of spaces and spatial imaginaries” He says that architects can help create these spaces and spatial imaginaries by “helping build communities charactered by racial and class heterogeneity, inclusion, and affordability.” (Lipsitz 2007, 20)

“Talking with presently poor and powerless people about what kinds of communities they would like to live in would enable land-use professionals to envision new spatial and social relations grounded in another kind expertise - the black spatial imaginary.” (Lipsitz 2007, 20)

“Public space also needs to be protected and enhanced…” He goes on to cite Robin D.G. Kelley’s argument that the “creation of private parks and the destruction of public play areas… are a small part of a larger project of racial subordination and suppression.” (Lipsitz 2007, 20)

I think Lipsitz’ interventions were more cutting in the decade he was writing them in. In our post-mandatory-diversity-and-racial-bias-training context, I’m not sure these are things we (stakeholders in various dimensions of urban development) don’t already know and don’t already do. In the context of Unity Park, affordable housing development was part of the plan, the entire park is designed on the premise of valuing racial and class heterogeneity, inclusion, and affordability. Park developers held listening sessions with members from the marginalized communities around the park and it seems that community leaders from these neighborhoods were pleased enough with the efforts to include their feedback. And the development is literally a public park. The values that Lipsitz idealizes in/of the Black spatial imaginary are valued and featured in the park’s development through the symbolic/commemorative landscape—literally showcasing the power of the Black community’s advocacy and honoring their resilience despite the imposition of the white spatial imaginary.

But the data does not lie. Dispossession and displacement of Black residents in the nearby historically Black neighborhoods that Unity Park seeks to redress is still significant. This either means that Lipsitz is wrong in his conceptualization of how to effectively address the white spatial imaginary or he couldn’t yet conceive of how ideology and rhetoric may be used to mimic those same values in the Black spatial imaginary to reinforce the white spatial imaginary. I’m choosing to argue the latter, but I think there’s more work to be done on how the social utility of memory can completely re-mechanize how people feel about a space despite measurable outcomes that show a conflicting narrative.

Conclusion

My ultimate point is simply that diversity ideology reinforces the white spatial imaginary. It can account for the more insidious ways that the white spatial imaginary can present and reinforce itself that Lipsitz did not write about in his 2007 and 2011 conceptualizations. In Lipsitz’ 2007 conceptualization of the white spatial imaginary he says, “racially exclusive neighborhoods, segregated suburbs, and guarded and gated communities comprise the privileged moral geography of the contemporary national landscape.” (Lipsitz 2007, 30) In our post-2020 context, multicultural/diversity ideology has replaced the colorblind racism ideology context that Lipsitz was writing from. I argue that the white spatial imaginary has only expanded beyond the most obvious segregated/exclusionary examples that Lipsitz presents, and I give you the case of Unity Park. Diversity ideology at play in the white spatial imaginary the illusion of representation, communal networks of care, and openness to advocacy and democratic deliberations. Diversity ideology superficially attaches itself to ideals present in Lipsitz’ conceptualization of the Black spatial imaginary, but doesn’t systemically and structurally commit to its investment. Diversity ideology reinforces the white spatial imaginary in a more insidious way than just through systemic exclusion, displacement, and dispossession as Lipsitz describes. Diversity ideology as imbedded in the physical built environment and social landscape of cities essentially gaslights citizens about the justice served and the current realities of social inequality.

What continues to perplex me about Unity Park is the prominent Black community leaders who so fiercely advocate for the park using rhetoric explicitly rooted in diversity ideology. How can Black community leaders stand on their word that the park is inclusive and a successful act of redress when clearly looking around at the drastically changing landscape and at the clear data that shows significant Black displacement and dispossession. Councilwoman Brock-Flemming is quoted addressing a group of protestors at the Unity Park unveiling, ““I don’t understand why some of y’all are upset, bless your heart, but you will get over it,” (Smith 2022) A quote stands out from Lipsitz:

[The white spatial imaginary] does not emerge simply or directly from the embodied identities of people who are white. It is inscribed in the physical contours of the places where we live, work, and play, and it is bolstered by financial rewards for whiteness. Not all white [people] endorse the white spatial imaginary, and some Black [people] embrace it and profit from it. Yet every white person benefits from the association of white places with privilege, from the neighborhood race effects that create unequal and unjust geographies of opportunity.” (Lipsitz 2007, 28)

More research will have to be done on the contradictory nature and consequences of Black people and diversity ideology, especially in the context of community building at/in community third spaces that draw on the past to create a sense of collective identity and narrative of social progress.

Works Cited & Referenced2

There are no commemorative efforts dedicated to Jesse Jackson or the students who challenged desegregation in Greenville (that I know of as of 12/26/24).

Clarke, Max and Fine, Gary A. 2010. “A for Apology: Slavery and the Collegiate Discourses of Remembrance—the Cases of Brown University and the University of Alabama” Indiana University Press 22(1):81-112

Eaker, Tara and Fletcher, Leslie. 2022. National Recreation and Park Association. https://www.nrpa.org/parks-recreation-magazine/2022/august/unity-park/

Espey M, Owusu-Edusei K. 2001. Neighborhood Parks and Residential Property Values in Greenville, South Carolina. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics. 33(3):487-492. doi:10.1017/S1074070800020952

Fine, Gary A. 2013. “Apology and Redress: Escaping the Dustbin of History in the Postsegregationalist South” Social Forces 19(4):1319-1340

Fitzgerald, Megan. 2024. “Path to Progress unveiled, telling the history of Greenville’s Unity Park” https://greenvillejournal.com/community/path-to-progress-unveiled-telling-the-history-of-greenvilles-unity-park/

Habron, G., Muthukrishan, S., & Timbes, A. 2024. Welcome to Greenville South Carolina: Urban Geography of Place. Southeastern Geographer, 64(3), 275-284.

Huff Jr, A. V. 2020. Greenville: the history of the city and county in the South Carolina Piedmont. Univ of South Carolina Press.

Kolb, Winiski, Hayes, Lippert. 2023. Racial Displacement in Greenville, SC. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/ec193fcd3f194bc0a7f8353f69f24aa8

Kolb, Ken. 2023. “Who gets to be revitalized in Greenville? How and why Furman studied racial displacement.” https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/opinion/2023/01/11/furman-university-how-why-studied-greenvilles-racial-displacement/69607211007/

Lipsitz, G. 2007. The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape. Landscape Journal, 26(1), 10–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43323751

Lipsitz, George. 2011. How Racism Takes Place. Temple University Press.

Mayorga-Gallo, S. (2019). The White-Centering Logic of Diversity Ideology. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(13), 1789-1809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219842619

Shi Institute for Sustainable Communities at Furman University. January 6, 2023. “Racial Change Near Unity Park” StoryMaps. Retrieved December 16, 2024. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c28d90d2557d4f47b15788c4215c8101

Smith, Evan Peter. 2022. “Unity Park Opens with a Splash” https://greenvillejournal.com/community/greenville-sc-unity-park-opens-with-a-splash/

Turick, Robert, Weems, Anthony, Swim, Nicholas, Bopp, Trevor, and Singer, John N. 2021. "Who Are We Honoring? Extending the Ebony & Ivy Discussion to Include Sports Facilities". Journal of Sport Management 35(1)17-29. <https://doi-org.libproxy.furman.edu/10.1123/jsm.2019-0303>.

Walters, Lindsey K. 2017. “Slavery and the American University: Discourses of Retrospective Justice at Harvard and Brown.” Slavery & Abolition 38(4): 719–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2017.1309875

WYFF News 4. May 19, 2022. “Unity Park leader Mary Duckett talks about park's history, future” YouTube Website. Retrieved December 16, 2024.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1996. “Social Memories: Steps to a Sociology of the Past” Qualitative Sociology 19(3):283-299

I swear this keeps coming up and hitting me in the face like a store bought banana creme pie, all because I have a label. So today I learned that GreenLink built a playground on its property as an unsolicited concession to the predominantly Black and Hispanic New Washington Heights neighborhood for taking away the public land that was part of the master plan for pedestrians space and low income housing. The playground is cheap and low quality. And it was built up against the road with no buffers, putting children in harm's way from traffic if the cheap-assed equipment doesn't first take out some wee'uns. GreenLink called it the New Washington Heights Playground - and when the neighborhood objected to the use of the name or the implication that the playground was a collaborative effort, GreenLink told neighborhood residents to pound sand. 😮

I keep "seeing" the 'white spatial imaginary" all over now that you have given me a name for it. The power of labels and names cannot be overstated. I've seen this in parks and the Confederate Museum, but I was talking this morning about Greenville's White Horse Road Corridor and how it is deadly for pedestrians because of many design issues, including the lack of lighting. Now maybe this is a car v. pedestrian conflict - but given the community around White Horse Road (the people who walk there) and the car-based traffic that passes through without otherwise being connected to that area, this is racially-biased space that is designed (much of it being neglectful design) to be hostile to and unsafe for Black residents. This is a sociological ear worm for me. I cannot get this out of my head and I can't stop seeing how much the 'white spatial imaginaries" pollute the community.